-

Winter 2025 Newsletter

Winter 2025 Newsletter -

Coffee House Industries Builds the First McLaren x Allwyn "Scratch Car" in Collaboration with Designer Florian Weber

Coffee House Industries Builds the First McLaren x Allwyn "Scratch Car" in Collaboration with Designer Florian Weber -

NEW ERA OF INDEPENDENT FILMMAKING IN ATLANTA

NEW ERA OF INDEPENDENT FILMMAKING IN ATLANTA -

Retreat to the Mountain, Return to Yourself

Retreat to the Mountain, Return to Yourself -

Five most common mistakes made by Producers......and how to avoid them!

Five most common mistakes made by Producers......and how to avoid them! -

Malibu Autobahn Puts Its Armored Truck to the Test

Malibu Autobahn Puts Its Armored Truck to the Test -

Announcing the BVA Final 2025 Auction!

Announcing the BVA Final 2025 Auction! -

New Arrivals

New Arrivals -

SmartSource Los Angeles Expands to New Facility

SmartSource Los Angeles Expands to New Facility -

Shoot Aviation Widebody for Apple TV's PLURIBUS

Shoot Aviation Widebody for Apple TV's PLURIBUS -

4Wall & Metro Media Productions Illuminate CNA's Global Nurses Solidarity Assembly

4Wall & Metro Media Productions Illuminate CNA's Global Nurses Solidarity Assembly -

The Lot at Formosa Wins Corporate Innovation Award

The Lot at Formosa Wins Corporate Innovation Award -

Coffee House Industries Brings MOONBOOT at ComplexCon Las Vegas

Coffee House Industries Brings MOONBOOT at ComplexCon Las Vegas -

The Board Patrol now carries Sand & Grass Protectors

The Board Patrol now carries Sand & Grass Protectors -

National Set Medics Celebrates 10 Years of Service!

National Set Medics Celebrates 10 Years of Service! -

Fall Newsletter

Fall Newsletter

Production News & Events -

In Memory of Otto Nemenz

In Memory of Otto Nemenz

(1941-2025)

A Legacy That Shaped Cinema -

Submissions are Now Open for the Society of Camera Operators (SOC) Camera Operator of the Year Film and Television and will Open November 5th for Technical Achievement Awards

Submissions are Now Open for the Society of Camera Operators (SOC) Camera Operator of the Year Film and Television and will Open November 5th for Technical Achievement Awards -

4Wall & GPJ Transform Domino Park for Historic Jeep Cherokee 2026 Reveal By 4Wall Entertainment

4Wall & GPJ Transform Domino Park for Historic Jeep Cherokee 2026 Reveal By 4Wall Entertainment -

GALPIN IS PROUD TO INTRODUCE OUR

GALPIN IS PROUD TO INTRODUCE OUR

NEW Production Supply Manager

John Vargas -

-

WonderWorks - Gateway To The Stars

WonderWorks - Gateway To The Stars -

WLA3D Produces Large Scale Models for Company Launch

WLA3D Produces Large Scale Models for Company Launch -

United Rentals Tool Solutions Powers Film & Production Communications

United Rentals Tool Solutions Powers Film & Production Communications -

-

Coffee House Industries Helps Bring Six Flags Fright Fest to Life

Coffee House Industries Helps Bring Six Flags Fright Fest to Life -

-

Newel Props, Film and TV Set Rentals in New York

Newel Props, Film and TV Set Rentals in New York -

From store racks to your home screen...

From store racks to your home screen...

Iguana Vintage Clothing is LIVE on WhatNot! -

-

Welcome to TCP Insurance: Trusted Coverage for the Creative Community

Welcome to TCP Insurance: Trusted Coverage for the Creative Community -

-

From Sketch to Spotlight: Coffee House Industries Brings the Canelo vs. Crawford Belt Display to Life in Record Time

From Sketch to Spotlight: Coffee House Industries Brings the Canelo vs. Crawford Belt Display to Life in Record Time -

The 25th Annual Valley Festival is Here Again

The 25th Annual Valley Festival is Here Again -

The Lot at Formosa: A Storied Studio's Next Chapter Unfolds

The Lot at Formosa: A Storied Studio's Next Chapter Unfolds -

2025 EMERGING CINEMATOGRAPHER AWARDS - LOS ANGELES!

2025 EMERGING CINEMATOGRAPHER AWARDS - LOS ANGELES! -

Producers are going BIG with Reel Monster Trucks

Producers are going BIG with Reel Monster Trucks -

-

-

-

California Rent A Car's Studio Division celebrates its 20th anniversary!

California Rent A Car's Studio Division celebrates its 20th anniversary! -

Showbiz Restrooms Brings Luxury to the Film Industry

Showbiz Restrooms Brings Luxury to the Film Industry -

FILM READY AVIATION MOCKUPS

FILM READY AVIATION MOCKUPS -

Here we Grow Again

Here we Grow Again -

From Blueprint to Reality: Heck Yeah Productions Unveils 5,000 Sq. Ft. Event and Recording Space

From Blueprint to Reality: Heck Yeah Productions Unveils 5,000 Sq. Ft. Event and Recording Space -

Quixote Provides Solar Power, Shared Smarter

Quixote Provides Solar Power, Shared Smarter -

Lights! Camera! aaaand GOLDENS at All Animal Actors International

Lights! Camera! aaaand GOLDENS at All Animal Actors International -

Baldwin Production Services San Francisco nominated for 2025 Cola Award

Baldwin Production Services San Francisco nominated for 2025 Cola Award -

Summer 2025 Newsletter

Summer 2025 Newsletter -

Keep Production in LA Industry Mixer Thursday Aug 21, 2024

Keep Production in LA Industry Mixer Thursday Aug 21, 2024 -

Creative Handbooks to be Given Out at the Upcoming Location Managers Guild International Awards

Creative Handbooks to be Given Out at the Upcoming Location Managers Guild International Awards -

-

Cape Town, Music Curation, Shout out & Podcast Interview VAMO

Cape Town, Music Curation, Shout out & Podcast Interview VAMO -

Get One-Stop Shopping on Fabric Printing & Borderless Framing

Get One-Stop Shopping on Fabric Printing & Borderless Framing -

OpenAI's New Browser Could Change the Internet Forever

OpenAI's New Browser Could Change the Internet Forever -

Malibu Autobahn Rolls Through LA with Joseline Hernandez for Zeus Network

Malibu Autobahn Rolls Through LA with Joseline Hernandez for Zeus Network -

Studio Animal Services, LLC - Kittens Available for Production

Studio Animal Services, LLC - Kittens Available for Production -

Wireless Teleprompter Rig Takes to the Streets of Midtown Manhattan

Wireless Teleprompter Rig Takes to the Streets of Midtown Manhattan -

-

New Everyday Low Prices on Rigging Hardware Take a Look at 20% Lower Prices on Average

New Everyday Low Prices on Rigging Hardware Take a Look at 20% Lower Prices on Average -

Westside Digital Mix: Venice Edition

Westside Digital Mix: Venice Edition -

Film in Palmdale

Film in Palmdale

Scenic Locations, Valuable Incentives -

Los Angeles Properties for

Los Angeles Properties for

Filming, Events, Activations

Pop Ups and Photo -

Burbank Stages can now be painted any color to match

Burbank Stages can now be painted any color to match -

Custom Prop Rentals: Bringing Your Dream Event to Life with Life-Size Magic

Custom Prop Rentals: Bringing Your Dream Event to Life with Life-Size Magic -

New Arrivals

New Arrivals -

-

Studio Wings moves offices, flight operations and aircraft to the Santa Fe Airport

Studio Wings moves offices, flight operations and aircraft to the Santa Fe Airport -

WeCutFoam Specializes in Fabrication of Signs, Logos and Letters for Company Summits

WeCutFoam Specializes in Fabrication of Signs, Logos and Letters for Company Summits -

Studio Tech Provides Wi-Fi And Internet for The Superman Movie Press Junket

Studio Tech Provides Wi-Fi And Internet for The Superman Movie Press Junket -

Superman movie Press Junket @ Buttercup Venues

Superman movie Press Junket @ Buttercup Venues -

Honoring Stories Worth Telling Since 2009

Honoring Stories Worth Telling Since 2009

All Ages - All Cultures - All Media -

Xenia Lappo Joins ESTA as New Program Manager for Membership & Events

Xenia Lappo Joins ESTA as New Program Manager for Membership & Events -

Nathan Wilson and Chris Connors discuss creating for children's television with ZEISS Supreme Prime lenses

Nathan Wilson and Chris Connors discuss creating for children's television with ZEISS Supreme Prime lenses -

Luxury Solar Restroom Trailer Sustainability

Luxury Solar Restroom Trailer Sustainability -

Midwest Rigging Intensive Returns with Touring Rigging Theme

Midwest Rigging Intensive Returns with Touring Rigging Theme -

Custom Pool Floats That Steal the Show

Custom Pool Floats That Steal the Show -

Malibu Autobahn Dresses Coachella 2025 for Shoreline Mafia

Malibu Autobahn Dresses Coachella 2025 for Shoreline Mafia -

Thunder Studios Wins Nine 2025 Telly Awards

Thunder Studios Wins Nine 2025 Telly Awards -

-

LCW Props Is Your One Stop Prop Shop

LCW Props Is Your One Stop Prop Shop -

Venues in Los Angeles for Activations and Filming

Venues in Los Angeles for Activations and Filming -

-

-

Honoring Stories Worth Telling Since 2009 - All Ages - All Cultures - All Media

Honoring Stories Worth Telling Since 2009 - All Ages - All Cultures - All Media -

Buttercup Venues Accepting Submissions to Help Property Owners Monetize Their Spaces

Buttercup Venues Accepting Submissions to Help Property Owners Monetize Their Spaces -

Studio Animal Services Stars in Latest Fancy Feast Commercial

Studio Animal Services Stars in Latest Fancy Feast Commercial -

WDM celebrates Summer at the famed Michael's Santa Monica

WDM celebrates Summer at the famed Michael's Santa Monica -

Studio Technical Services Inc.

Studio Technical Services Inc.

Spring 2025 Newsletter -

From Call to Setup: Coffee House Industries Lights Up Netflix Is a Joke at the Avalon

From Call to Setup: Coffee House Industries Lights Up Netflix Is a Joke at the Avalon -

WLA3D produces scale model for Fox Grip

WLA3D produces scale model for Fox Grip -

Filming Locations and Event Venues Los Angeles

Filming Locations and Event Venues Los Angeles -

Scenic Expressions Launches a Full-Service Liquidation Solution for the Film & TV Industry

Scenic Expressions Launches a Full-Service Liquidation Solution for the Film & TV Industry -

Producers Need Reel Monster Trucks for Reel Productions

Producers Need Reel Monster Trucks for Reel Productions -

Meet Michael Way | Engineer

Meet Michael Way | Engineer -

In Development: ZEISS Virtual Lens Technology Elevating VFX with physically based lens effects

In Development: ZEISS Virtual Lens Technology Elevating VFX with physically based lens effects -

(2) PREMIER AV ACTIONS

(2) PREMIER AV ACTIONS -

RSVP - 80 Films & Tech - Meet the Visionaries - EMMY, Telly, Peabody winners and more

RSVP - 80 Films & Tech - Meet the Visionaries - EMMY, Telly, Peabody winners and more -

New Arrivals Are Here - Check Out LMTreasures.com

New Arrivals Are Here - Check Out LMTreasures.com -

Film-Friendly Retail Space at Tejon Outlets

Film-Friendly Retail Space at Tejon Outlets -

Behind Every Great Production, There's a Great Move

Behind Every Great Production, There's a Great Move -

Buttercup Venues' recent work with Invisible Dynamics & Blue Revolver

Buttercup Venues' recent work with Invisible Dynamics & Blue Revolver -

Join ZEISS Cinema at this year's NJ Film Expo on Thursday, May 1

Join ZEISS Cinema at this year's NJ Film Expo on Thursday, May 1 -

The Location Managers Guild International (LMGI) announces that its 12th Annual LMGI Awards Show will be held on Saturday, August 23, 2025

The Location Managers Guild International (LMGI) announces that its 12th Annual LMGI Awards Show will be held on Saturday, August 23, 2025 -

Get Your Production Supplies Now While Prices Are Stable*

Get Your Production Supplies Now While Prices Are Stable*

Rose Brand Is Your One Stop Shop -

Immersive Sound for your next production from TrueSPL

Immersive Sound for your next production from TrueSPL -

WeCutFoam Fabricating Large Scale Props and Decor for Companies & Products Launching Events

WeCutFoam Fabricating Large Scale Props and Decor for Companies & Products Launching Events -

The "CA-Creates" eGroup Network

The "CA-Creates" eGroup Network -

The Location Managers Guild International Announces the Newly Elected 2025 LMGI Board of Directors

The Location Managers Guild International Announces the Newly Elected 2025 LMGI Board of Directors -

Production Moves: How to Find the Most Qualified Mover

Production Moves: How to Find the Most Qualified Mover -

SAG-AFTRA Talent Payments @ Production Payroll Services

SAG-AFTRA Talent Payments @ Production Payroll Services -

-

-

New Everyday Low Prices on Rigging Hardware

New Everyday Low Prices on Rigging Hardware

Take a Look at 20% Lower Prices on Average -

Tejon Ranch introduces its Premium Ranch Cabins

Tejon Ranch introduces its Premium Ranch Cabins -

Our Enchanting Garden Collection is Growing!

Our Enchanting Garden Collection is Growing! -

-

-

Top Entertainment CEOs & Industry Titans Join Forces for Groundbreaking New Media Film Festival®

Top Entertainment CEOs & Industry Titans Join Forces for Groundbreaking New Media Film Festival® -

Tejon Ranch opens Diner location for your next Production

Tejon Ranch opens Diner location for your next Production -

Discover the Performance of ZEISS Otus ML

Discover the Performance of ZEISS Otus ML

Deep Dive into the Features and Technology -

Universal Animals cast the dog in Anora!

Universal Animals cast the dog in Anora! -

Burbank Stages is Now Open with upgraded support space

Burbank Stages is Now Open with upgraded support space -

-

Buttercup Venues Grows Portfolio with Exciting New Locations for Filming and Events

Buttercup Venues Grows Portfolio with Exciting New Locations for Filming and Events -

Fashion District Suite 301

Fashion District Suite 301 -

Something new is coming for Photographers

Something new is coming for Photographers

Mark Your Calendar - February 25th -

WLA3D completes scale model of vintage Knott's Berry Farm attraction

WLA3D completes scale model of vintage Knott's Berry Farm attraction -

New Media Film Festival has invited you to submit your work via FilmFreeway!

New Media Film Festival has invited you to submit your work via FilmFreeway! -

WeCutFoam Collaborated Once More with Children's Miracle Network Hospitals

WeCutFoam Collaborated Once More with Children's Miracle Network Hospitals -

-

EigRig SLIDE-R1 Revolutionizes Filmmaking Production with Innovation

EigRig SLIDE-R1 Revolutionizes Filmmaking Production with Innovation -

-

-

-

Practicals Rental Lighting Welcomes the Jucolor UV Flatbed Printer

Practicals Rental Lighting Welcomes the Jucolor UV Flatbed Printer -

GBH Maintenance Inc. Has Grown

GBH Maintenance Inc. Has Grown -

The Rarest Stars Shine Brightest

The Rarest Stars Shine Brightest -

Affected by the ongoing California wildfires

Affected by the ongoing California wildfires -

Get One-Stop Shopping...

Get One-Stop Shopping... -

Buttercup Venues Expands

Buttercup Venues Expands -

-

Los Angeles Office Spaces: Versatile Backdrops for Filming

Los Angeles Office Spaces: Versatile Backdrops for Filming -

All Creatures Great and small holiday commercial for Montefiore hospital

All Creatures Great and small holiday commercial for Montefiore hospital -

DEEP CLEANS WAREHOUSE FOR SUPER BOWL COMMERCIAL

DEEP CLEANS WAREHOUSE FOR SUPER BOWL COMMERCIAL -

New Production Hub in Los Angeles

New Production Hub in Los Angeles -

Carlos R. Diazmuñoz

Carlos R. Diazmuñoz -

WeCutFoam Specializes in Decor

WeCutFoam Specializes in Decor -

Studio Technical Services Inc.

Studio Technical Services Inc.

Fall 2024 Update -

New Media Film Festival has invited you to submit your work

New Media Film Festival has invited you to submit your work -

-

Available again!

Available again!

Studio 301 - 16,000 Sq. Ft. -

Elevate Your Production with SoundPressure Labs'

Elevate Your Production with SoundPressure Labs' -

Pro-Cam expands rental operation...

Pro-Cam expands rental operation... -

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF LATINO INDEPENDENT PRODUCERS

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF LATINO INDEPENDENT PRODUCERS -

New Sony A9 III Reviews

New Sony A9 III Reviews -

New, Heavyweight, Lustrous, Shimmering 56" Elana IFR Fabric

New, Heavyweight, Lustrous, Shimmering 56" Elana IFR Fabric -

JOIN US IN ORLANDO THIS NOVEMBER!

JOIN US IN ORLANDO THIS NOVEMBER! -

BLUE MOON CLEANING

BLUE MOON CLEANING

RESTORES MUSIC-MAKING -

Another Collaboration Between WeCutFoam and Event Planner

Another Collaboration Between WeCutFoam and Event Planner -

BLUE MOON CONGRATULATES 2024 COLA FINALISTS

BLUE MOON CONGRATULATES 2024 COLA FINALISTS -

Fall Production News & Events

Fall Production News & Events -

Not just green, but mighty Verde

Not just green, but mighty Verde -

Introducing...

Introducing...

Restaurant/Bar/Venue in Encino -

-

ESTA and Earl Girls, Inc. Launch $100,000 TSP Fundraising Challenge

ESTA and Earl Girls, Inc. Launch $100,000 TSP Fundraising Challenge -

There's still time to register for ESTA's Plugfest

There's still time to register for ESTA's Plugfest -

-

BLUE MOON CLEANING SEES SPIKE IN MAJOR LA FEATURE FILMING

BLUE MOON CLEANING SEES SPIKE IN MAJOR LA FEATURE FILMING -

Amoeba Records on Sunset

&

SuperMarket in K-Town -

"Alice in Wonderland" tea party brought to life...

"Alice in Wonderland" tea party brought to life... -

Filming With Production Ready Aviation Equipment

Filming With Production Ready Aviation Equipment -

-

-

A5 Events - Take Your Event to The Next Level

A5 Events - Take Your Event to The Next Level -

The Original Amoeba Records Venue

The Original Amoeba Records Venue

& The SuperMarket -

Doc Filmmaker Jennifer Cox

Doc Filmmaker Jennifer Cox -

Red, White or Blue Rental Drapes

Red, White or Blue Rental Drapes -

Introducing Tuck Track Invisible Framing for Fabric Prints

Introducing Tuck Track Invisible Framing for Fabric Prints -

-

American Movie Company's LED Wall Studio Sale

American Movie Company's LED Wall Studio Sale -

Black 360 Independence Studio

Black 360 Independence Studio -

Nominations are open for the 2025 ESTA Board of Directors!

Nominations are open for the 2025 ESTA Board of Directors! -

Custom Prop Rentals is moving to a new, larger location!

Custom Prop Rentals is moving to a new, larger location! -

Pro-Cam opens Las Vegas branch, expanding rental operation

Pro-Cam opens Las Vegas branch, expanding rental operation -

New ShowLED Starlight Drops

New ShowLED Starlight Drops -

Costume House Sidewalk Sale

Costume House Sidewalk Sale -

Working Wildlife's newly renovated 60 acre ranch available for Filming

Working Wildlife's newly renovated 60 acre ranch available for Filming -

Location Manager Bill Bowling

Location Manager Bill Bowling

to Receive the Trailblazer Award -

-

Mr. Location Scout is in Lake Tahoe

Mr. Location Scout is in Lake Tahoe -

DreamMore Resort Fountain

DreamMore Resort Fountain -

Valley Film Festival

Valley Film Festival

Greetings from the (818): -

2024 Changemaker Awards and Artist Development Showcase

2024 Changemaker Awards and Artist Development Showcase -

ZEISS Conversations with Jack Schurman

ZEISS Conversations with Jack Schurman -

Collaboration Between WeCutFoam and Yaamava Resort & Casino

Collaboration Between WeCutFoam and Yaamava Resort & Casino -

Location Managers Guild International Awards

Location Managers Guild International Awards -

Molding Cloth

Molding Cloth

Make Fabulous Textured Designs -

WeCutFoam Specializes in Large Events

WeCutFoam Specializes in Large Events -

Introducing Truck Track Invisible Framing for Fabric Prints

Introducing Truck Track Invisible Framing for Fabric Prints -

GBH Maintenance is back at Herzog Wine Cellars

GBH Maintenance is back at Herzog Wine Cellars -

SATE NORTH AMERICA 2024

SATE NORTH AMERICA 2024 -

Production News & Events Summer Edition

Production News & Events Summer Edition -

Four Amazing Architectural Locations!

Four Amazing Architectural Locations! -

* BIG SAVINGS * ON BIG STUDIOS

* BIG SAVINGS * ON BIG STUDIOS -

Let Your Brand Stand Tall!

Let Your Brand Stand Tall! -

Sue Quinn to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award

Sue Quinn to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award -

ZEISS Cinema at Filmscape Chicago

ZEISS Cinema at Filmscape Chicago -

GBH Maintenance Is the Standard for Commercial Maintenance

GBH Maintenance Is the Standard for Commercial Maintenance -

Come Join Us at Cine Gear Expo 2024

Come Join Us at Cine Gear Expo 2024 -

Available now:

Available now:

6th Street Gallery & Venue -

Thunder Studios Triumphs with Five Telly Awards

Thunder Studios Triumphs with Five Telly Awards -

Reddit Went Public IPO - WeCutFoam Was There With Decor

Reddit Went Public IPO - WeCutFoam Was There With Decor -

AirDD's Hottest New Product

AirDD's Hottest New Product

for 2024 Events -

GBH Maintenance Sets the Standard for Window Cleaning

GBH Maintenance Sets the Standard for Window Cleaning -

Haigwood Studios collaboration with the UGA Dodd School of Art

Haigwood Studios collaboration with the UGA Dodd School of Art -

-

RX GOES TO 11!

RX GOES TO 11!

with Mike Rozett -

Don't Be A Square - Think Outside The Box!!

Don't Be A Square - Think Outside The Box!! -

WeCutFoam Fabricates Realistic Lifesize Props

WeCutFoam Fabricates Realistic Lifesize Props -

-

Exposition Park Stage/Venue

Exposition Park Stage/Venue -

Production Update From UpState California Film Commission

Production Update From UpState California Film Commission -

Base Camp With All The Extras

Base Camp With All The Extras -

LAPPG AT THE ZEISS CINEMA SHOWROOM

LAPPG AT THE ZEISS CINEMA SHOWROOM -

ZEISS Nano Primes and ZEISS CinCraft Scenario Received NAB Show 2024

ZEISS Nano Primes and ZEISS CinCraft Scenario Received NAB Show 2024 -

Cranium Camera Cranes Introduces the all new Tankno Crane!

Cranium Camera Cranes Introduces the all new Tankno Crane! -

Come Join Us at Cine Gear Expo 2024

Come Join Us at Cine Gear Expo 2024 -

FAA Drill Burbank Airport

FAA Drill Burbank Airport

(federal aviation administration) -

Exclusive Stahl Substitute Listing from Toni Maier-On Location, Inc.

Exclusive Stahl Substitute Listing from Toni Maier-On Location, Inc. -

GBH Maintenance: Elevating Janitorial Standards Across Los Angeles

GBH Maintenance: Elevating Janitorial Standards Across Los Angeles -

LOCATION CONNECTION has the best RANCHES FOR FILMING!

LOCATION CONNECTION has the best RANCHES FOR FILMING! -

Hollywood Studio Gallery has Moved

Hollywood Studio Gallery has Moved -

AirDD's inflatable "Kraken" designs transformed Masked Singers

AirDD's inflatable "Kraken" designs transformed Masked Singers -

GBH maintenance Provided a Hollywood Shine for Herzog Wine Cellars

GBH maintenance Provided a Hollywood Shine for Herzog Wine Cellars -

Production News & Events

Production News & Events

Spring Newsletter -

Immersive Venue/ Black Box/ Stage

Immersive Venue/ Black Box/ Stage

2024 DTLA Arts District -

-

Exclusive Malibu Listing from Toni Maier - On Location, Inc.

Exclusive Malibu Listing from Toni Maier - On Location, Inc. -

Empowered Collaborates with Harlequin Floors

Empowered Collaborates with Harlequin Floors -

Movie Premiere, TCL Chinese Theater

Movie Premiere, TCL Chinese Theater -

Studio Tech provides services for the Grammy House

Studio Tech provides services for the Grammy House -

Sora AI Text To Video

Sora AI Text To Video -

New Apex Photo Studios

New Apex Photo Studios

Website: Rent Smarter, Create More & earn rewards! -

-

How Ideal Sets Founder Harry Hou Cracked the Code on Affordable Standing Sets

How Ideal Sets Founder Harry Hou Cracked the Code on Affordable Standing Sets -

New Storage & Co-Working Spaces In Boyle Heights near Studios

New Storage & Co-Working Spaces In Boyle Heights near Studios

For Short or long term rental -

Auroris X Lands at A Very Good Space

Auroris X Lands at A Very Good Space -

GBH Maintenance Completes Work on 33000ft Production Space

GBH Maintenance Completes Work on 33000ft Production Space -

MUSICIAN ZIGGY MARLEY IS ANOTHER HAPPY.CUSTOMER OF MAILBOX TOLUCA LAKE'S 'DR. VOICE'

MUSICIAN ZIGGY MARLEY IS ANOTHER HAPPY.CUSTOMER OF MAILBOX TOLUCA LAKE'S 'DR. VOICE' -

Custom Digitally Printed Commencement Banners & Backdrops

Custom Digitally Printed Commencement Banners & Backdrops -

Rose Brand, SGM, Bill Sapsis, Sapsis Rigging, and Harlequin Floors Sponsor NATEAC Events

Rose Brand, SGM, Bill Sapsis, Sapsis Rigging, and Harlequin Floors Sponsor NATEAC Events -

Kitty Halftime Show air for Animal Planet's Puppy Bowl

Kitty Halftime Show air for Animal Planet's Puppy Bowl -

Georgia Animal Actors Persents Merlin

Georgia Animal Actors Persents Merlin -

ESTA Launches Revamped NATEAC Website

ESTA Launches Revamped NATEAC Website -

Mollie's Locations

Mollie's Locations -

ZEISS Cinema News for February

ZEISS Cinema News for February -

-

Seamless Fabric Backdrops up to 140ft x 16ft, Printed Floors...

Seamless Fabric Backdrops up to 140ft x 16ft, Printed Floors... -

Check out all the Pioneer Gear at Astro!

Check out all the Pioneer Gear at Astro! -

Production News & Events

Production News & Events -

All of Your Production Supplies Gathered in Just One Place

All of Your Production Supplies Gathered in Just One Place -

Meet the RED V-Raptor [X]

Meet the RED V-Raptor [X] -

Sit Back and Enjoy Some Laughs

Sit Back and Enjoy Some Laughs -

Mr. Location Scout Scouted and Managed Locations

Mr. Location Scout Scouted and Managed Locations -

Introducing...

Introducing...

Landmark Restaurant in Encino -

The White Owl Studio is celebrating all that is new!

The White Owl Studio is celebrating all that is new! -

-

Last Call for NATEAC 2024 Proposals

Last Call for NATEAC 2024 Proposals -

NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED FOR THE

NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED FOR THE

2024 MUAHS -

Voted Best New Stage Rigging Products at LDI 2023

Voted Best New Stage Rigging Products at LDI 2023 -

NEED MORE SPARKLE IN THE FLOOR?

NEED MORE SPARKLE IN THE FLOOR? -

David Panfili to Appoint Michael Paul as President of Location Sound Corp.

David Panfili to Appoint Michael Paul as President of Location Sound Corp.

industry news

The Latest Industry News for the Exciting World of Production.

Creative Handbook puts together a bi-monthly newsletter featuring

up-to-date information on events, news and industry changes.

Add My Email

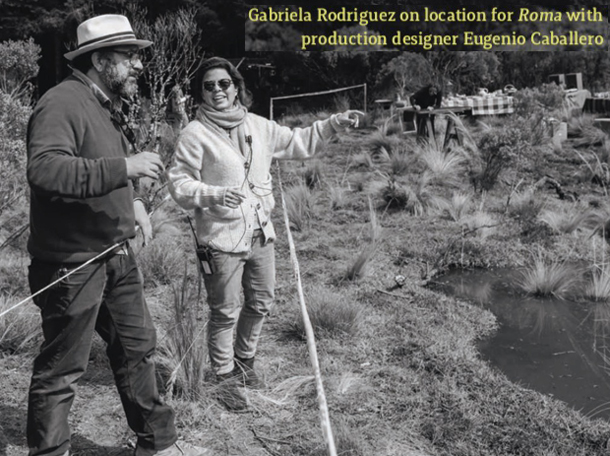

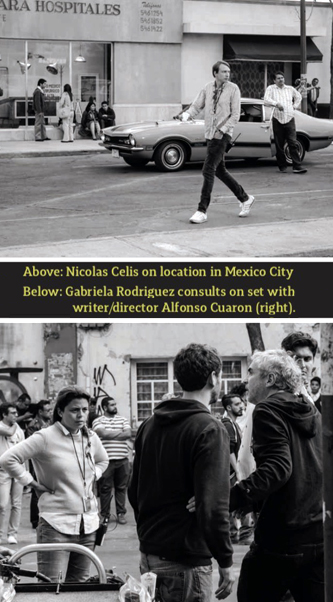

No Script? No Problem - "Roma" Wasn't Built In A Day - Or With A Script

By: Producers Guild of America | February 4, 2019

Email This Article |  |

|

No Script? No Problem - "Roma" Wasn't Built In A Day - Or With A Script

Nearly every film director who's known for being a true master of their craft has a personal film up their sleeve that longs to get out. Typically these intimate and compelling films are showcased at the beginning of their careers. The filmmakers are catapulted to fame and elevated to bigger budgets, bigger stories, bigger stars-so much so, they never quite get back to their roots, seduced by the rewards of Hollywood success. However once in a while the stars line up, and that special story they've held close to their heart sees the light of day. Think Bergman's Cries and Whispers (1972), or Louis Malle's Au Revoir, Les Enfants (1987). Sometimes the timing is right and voila! A masterpiece is born.

Alfonso Cuarón's Roma stands in that lineage. A highly personal, semi-autobiographical memoir of growing up in Mexico City in the 1970s, raised by his mother and their live-in housekeeper, this intimate film will be among the first beneficiaries of Netflix's new awards release strategy, receiving limited theatrical exhibition before appearing on their streaming platform. One of the season's most eagerly awaited films, it's already taken the festival circuit by storm. That success is in no small part thanks to its producers, Gabriela Rodriguez and Nicolás Celis.

After having won an Oscar for Gravity in 2013 and known for relatively dark, large-canvas features such as Children of Men (2006) and Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004), Cuarón returned to his Mexican roots for a highly unconventional production. He hasn't directed a Spanish-language film since Y Tu Mamá También (2001).

The story of Roma started percolating 12 years ago. Two years before that, a young intern joined his company, Esperanto Films, in New York City. She had just graduated film school and was anxious to work in production. Gabriela Rodriquez hails from Venezuela and has been with Esperanto for her entire career. After interning, she became Cuarón's personal assistant before her promotion to running the company itself. She has worked by his side through his biggest successes. So when Cuarón approached her to produce his passion project, telling her she was "ready to do this," she all but had to say, "yes"-though she admits she was apprehensive, "because I know what letting him down feels like," she confides.

Meanwhile Nicolás Celis has been working in Mexico as a producer and unit production manager for more than 12 years, collaborating with such Mexican directors as Tatiana Huezo and Amat Escalante. He found his way into Cuarón's orbit when he produced Desierto (2015), the feature film debut of Cuarón's son, Jonás. Aside from a few phone calls during Desierto, Gaby and Nico (as they came to be known), never worked together until Roma. They quickly found out that one was the yin to the other's yang. Celis loves dealing with people, aligning the Mexican officials to get on board, though none of them had read the script or even known that it was Cuarón's movie until later. Meanwhile Rodriquez knew the director intimately, understood what he needed and, even more importantly, knew what she needed to do to stay one step ahead and keep him focused. On this shoot Cuarón wore many hats. He, too, was a producer but he also served as director, writer, cinematographer and editor. With so many roles to play, he needed both Celis and Rodriquez to make production happen while he worried about the actors, lights and camera angles. Fortunately neither of his fellow producers was afraid to get in the kitchen and do whatever was necessary to make his creative vision a reality.

Cuarón moved his company to Mexico nearly three years ago to begin pre-production on Roma, which lasted more than 10 months. A long prep allowed the producers to research every aspect of the director's early life in Mexico City, right down to the family dog, Borras. All the research came in lieu of breaking down the script ... because they had no script. Cuarón shared the script with just one person-David Linde from Participant Media, who financed the film and served as an executive producer on it. (We only hope Linde was up on his Spanish. Cuarón provided no translation.) Cuarón's intense secrecy was a safeguard against anyone slipping pages to the cast. He would be working with a lot of non-actors in addition to well-known Mexican talent and wanted the process to be fresh and something he alone had control over. It was the producers' job to allow him his creative process while still prepping the production as best they could.

"We all agreed to participate on this project without a script," Rodriquez tells me over a cappuccino at The London Hotel. "It's like when a kid is told he's not going to have any more cookies. At some point you realize, even if you're crying, you're not going to get the cookie. Let's just see how you get on with your day without the cookie. That's kind of how we felt." The team was compensated with the extremely long pre-production period to provide the time for research, scouting and consulting with the director, discussing shots and scenes. Their location scouts grew bigger and bigger, sometimes bringing in excess of 30 people on a scout. They wanted every department represented at the earliest stage so Cuarón could explain what he would need from them. They had a skeleton of dates, so they knew on a given span of days they were going to shoot "the riot," while on another day they would be shooting "the birth scene." They were still given zero dialogue.

Hiring a team of collaborators to shoot a script that no one was allowed to read created its own set of problems. Those fell to Celis to solve. "I remember during the first meeting I met Alfonso, I asked him, who's going to be the script supervisor? After all this is someone who works closely with the director. Then when we didn't have a script-it was like, how are we going to hire a script supervisor if we won't give her the script? Even the [job title] says it!" When it came time to interview Natalia Moguel, he asked, "Hey, are you willing to work without a script?" Moguel naturally asked Celis what he meant. Nonchalantly Celis told her, "Yeah, yeah, we do have a script, but we haven't read it, so you're not going to read it either. So are you willing to do it?" As everyone did on this shoot, Moguel decided to trust the process, trust her belief in Cuarón and gave it her all. In Moguel's case, that meant developing a completely new way of tracking blocking and continuity without it.

"Once we knew this was the way we were going to operate, we knew we had to be ready for everything," Rodriguez explains. "So we have our wardrobe truck. We have it there all the time. We have backups. It sounds crazy but it's the way we gave Alfonso the freedom for his creative process to flow in case it needed to take a different direction, which it rarely did."

"Once we knew this was the way we were going to operate, we knew we had to be ready for everything," Rodriguez explains. "So we have our wardrobe truck. We have it there all the time. We have backups. It sounds crazy but it's the way we gave Alfonso the freedom for his creative process to flow in case it needed to take a different direction, which it rarely did."In addition to shooting without a script, Roma also shot in story sequence, which presented another series of problems. But there were plenty of happy accidents that happened along the way. Celis notes that the house they found was an exact replica of Cuarón's childhood home in his old neighborhood, which gives the film its title. It served ideally as a stage, given that the owner told them he was planning to demolish it, so the team could do what they wanted to the structure as long as they left him the lot in good shape. Rodriguez and Celis took full advantage of the permission to knock down walls and open up ceilings without having to put them back in working order.

Cuarón's creative vision lived its details. Everything had to be as it was in 1970, down to the clothes and shoes that the thousand-plus extras wore during the riot scene. A big avenue leading to the cinema as well as a street where the mother is stuck between two big trucks all had to be built, because so much had changed in the urban landscape, mostly due to the earthquake and modern technology.

"I think it was the biggest set ever built in Mexico. But I cannot guarantee that," Celis laughs. "But since I've been working, I've never seen such big construction." Rodriguez confirms that the size of the set took up roughly four city blocks.

The producers and their crew learned to push past what they thought were their limitations. Creating hailstones for a storm scene was another adventure. Cuarón wasn't happy with the fake hail available in Mexico because, while the stones could be different sizes, they were still all the same shape-in other words, not authentic enough to meet Cuarón's standards. There was a company from Canada that made it perfectly, but their work was very expensive. Rather than saying "no" to the director, the producers created a "hail unit" and tried to figure out how to engineer Cuarón-approved hailstones. The production manager came up with the idea of cutting up glue sticks, then melting them a little on hot metal, to create individual, unique hailstones. Rodriguez recalls, "One day Alfonso walks in the office to find five people from production literally sitting there with buckets, cutting glue, dropping them into the buckets, and then those buckets would go out to the truckers who helped us burn them into the different shapes and then those went into a different bucket ... hail-making!" Two hundred kilos of glue sticks later, they had their handcrafted hail.

That effort was typical of the team's "Anything for Alfonso" approach. As Celis explains, "If he had an idea he really liked, we tried to make it happen, find the means. That's something I really learned for life, that sometimes something looks like a mountain you will never be able to climb by any reason or any excuse you might find. But [Cuarón] really pushed us to find the tools to do it and find the way I think this could be solved. He makes you, instead of saying 'no,' to be ready with alternatives, always."

"I don't believe he is a director that separates himself from stories," Rodriguez reflects. "He really does nurture them, carry them and work with them from beginning to end. But I think, in this one, even while he trusted us and said, 'Go ahead-this is what I want, I trust that you will make it happen,' he also had to trust himself even more to say, 'I'm going to do this the way I'm going to do this.' He wasn't expecting anyone to necessarily love or hate it. He wasn't thinking about how to market it while he was making it. He was just thinking, 'This is my process and I'm going to do it' ... and that takes courage. When you're already in that place when you have the commercial and critical success-all that hoopla that's generated from everyone telling you you're great-it takes some courage to say, 'OK. I'm going to do this and whatever happens, I'm going to be OK with it.'"

The buzz surrounding the film is just icing on the cake for these two producers. They put one foot in front of the other, enjoying every step of the process, even when it was daunting. Now they are reaping the unexpected fruits of their labors and find themselves delighted by the amazing reception Roma has received. "I'm super excited with this movie," proclaims Celis. "That it's in black and white, that it's in Spanish ... That all of this is happening, for everybody. It's 'The Little Engine That Could'! We just never expected it to blow up and that people would identify with and find it so accessible."

"To me," Rodriguez continues, "that this has been received the way it has around the world ... I thought Latin America would get it, but the reception worldwide-wow-this is already so much more than I was expecting."

To top it off, this young, self-effacing woman, who has worked long and hard for Alfonso Cuarón, may very well become the first Latina woman to be nominated for a Best Picture Oscar. "I feel grateful for the opportunity," she says, "and grateful for the faith that Alfonso put on me to push me and not give me a choice or a way out. The fact that there's a movie out there and it's finished-it's there! We did it! That means the most. To me, what I learned is that I can do it." Both producers reminded me that Roma spelled backwards is Amor-an appropriate grace note that sums up the entire crew's feeling for the unique production.

No Comments

Post Comment